An Eddic Fairy-tale of a Cursed Princess: An Edition of Vambarljóð

Haukur Þorgeirsson

Article keywords:

Abstract

The Eddic fairy-tales are a group of poems of medieval origin which were collected from oral tradition in Iceland in the seventeenth century and later. These poems employ an Icelandic version of the Germanic alliterative metre and make use of Eddic formulas and style. They have fairy-tale subjects with evil stepmothers, elves, ogresses, curses and other supernatural elements. A striking trait of these poems is their emphasis on female characters and perspectives. The poem here edited is Vambarljóð, which tells of Signý, a resourceful princess cursed by her stepmother to appear as a cow’s stomach. The poem was collected three times from oral tradition. One version (V) survives as part of a late seventeenth-century collection of ballads and other popular poems. Two other versions are fragmentary: one of them (Þ) was written down for Árni Magnússon (1663–1730) and the other (J) by one of Árni’s successors. The most complete version, V, is also the one that has the most archaic appearance and probably best reflects the poem’s medieval origins. The three versions are edited separately here. Later poems and prose narratives of the same tale type are also briefly described.ORCID iD: 0000-0002-7872-0601

ISSN: Print 2754-4575

ISSN: Online 2754-4583

DOI: 10.57686/256204/32

© 2023 Haukur Þorgeirsson

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (CC BY)![]()

Introduction

In seventeenth-century Iceland it became fashionable to collect folk-poetry from oral tradition.1 Most of the poems thus recorded are ballads, many of them of medieval origin and with close analogues in the Faroe Islands and mainland Scandinavia.2 But along with these, the folk-poem collections also contain a few works of another genre, the Eddic fairy-tales.3 These are narrative poems with fairy-tale motifs composed in the Icelandic version of the Germanic alliterative metre. Only eight of these poems have come down to us but some exist in more than one version, including Vambarljóð, which is edited here.

A striking feature of the Eddic fairy-tales is their wealth of poetic formulas, many of which they share with the Eddic poems of the Codex Regius and other medieval poetry. Jón Helgason argued that the Eddic fairy-tales represent a direct continuation of the Eddic tradition.4 There are good reasons to believe that this is true. The popular subject matter and the oral preservation are factors which suggest a continuous tradition rather than later learned imitations.5 The strong emphasis which these poems have on female characters and perspectives is also unlike the typical products of the educated elite but in keeping with Eddic poems such as Oddrúnargrátr and the Guðrúnarkviður.

Vambarljóð tells the story of Signý Hringsdóttir, a princess cursed by her evil stepmother to have the shape of a stomach (vömb). Signý takes to being a monster with gusto and there is some charm in the ruthlessness with which she forces a prince into marrying her to undo the curse. In one stanza, Signý taunts the prince for crying on his wedding day, pointing out that many brides are sad when they enter into marriage but an unhappy groom is a novelty. The stanza appears to call attention to a certain subversion or role-reversal in the narrative and may have been salient to the audience of the poem since it is one of a small handful to be preserved in all three versions edited here.

Vambarljóð was published along with the other Eddic fairy-tales by Ólafur Davíðsson in 1898 but that edition leaves much to be desired and was not based on all surviving manuscripts.6 In the current edition, three versions are separately edited and translated. The V version tells a complete story while the Þ and J versions are fragmentary. These versions have enough textual overlap to be seen as the same poem but they are so different that an edition with one base text and variants would not do them justice.

There exists a fourth version (L) of Vambarljóð which is significantly longer than the other three. It tells the same story but shares only very few lines with any of the other versions. This longer text is not edited here but I include some analysis of it which indicates that it is of post-medieval origin — perhaps best seen as a new composition based on the old poem rather than a variant of it. The story of Signý is also preserved in two versions in rímur style (rhymed epic) as well as a prose fairy-tale version collected in the nineteenth century. It was a productive story for a long time.

The first collector

Students of Old Norse literature know the efforts undertaken by bishop Brynjólfur Sveinsson (1605–75) to gather and transmit the medieval literature of Iceland. His most famous accomplishment is acquiring the Codex Regius of the Eddic poems, which he sent to his sovereign, Frederick III of Denmark, in 1662. Few know that around the same time, Brynjólfur’s younger brother Gissur also set out to collect medieval poems, but for a different purpose and with a different method — not from old vellum but from the lips of the people.

The manuscripts which preserve most of the Eddic fairy-tales are collections of fornkvæði, ‘poems of old’. These collections mostly contain ballads in the same simple end-rhymed poetic form as was popular in the Faroe Islands and mainland Scandinavia. For this reason, the word fornkvæði is sometimes translated as ‘ballad’ but this may cause some confusion since the Icelandic word had a wider sense. The first known collector of fornkvæði was Gissur Sveinsson (1604–83), a clergyman in the West Fjords. Gissur’s collection survives in his own autograph copy, AM 147 8vo (G), which originally contained 71 numbered poems. The title page of the book notes that it is ‘til gamans og skiemtunar ad lesa’ (‘to be read for enjoyment and entertainment’) and the first page reiterates this with the heading ‘Nøckur fornnkvæde til gamans’ (‘Some fornkvæði to enjoy’). Gissur and the other seventeenth-century collectors aimed to collect enjoyable poetry and their primary objectives were not philological or historical.7 Some examples will give an idea of the contents of Gissur’s book and the Icelandic ballad tradition.

Poem 1 is Kvæði af Magnúsi Jónssyni, known only from Iceland and the Faroe Islands. The titular character proposes to two women and ends up paying for that with his life. Vésteinn Ólason describes the ballad’s ‘clumsy’ style as ‘characteristic of ballads which have come late to Iceland’, suggesting the sixteenth century as a possibility.8

Poem 2 is Kvæði af Tófu og Suffaralín, a medieval ballad, known from all the Nordic countries.9 The characters are historical — King Valdemar the Great of Denmark (1131–82), his queen Sophia (‘Suffaralín’) and his mistress Tove. As in poem 1, the subject is a love triangle, followed by a murder. In this case, the queen kills the mistress.

Poem 7 is Kvæði af Ólafi liljurós. This is the only medieval ballad which is still popularly sung in Iceland. It tells of a knight’s meeting with some elf-maidens who invite him to live with them. The knight says that he would rather keep his faith in Christ. One of the elf-maidens then asks him for a parting kiss and as he obliges, she kills him with a sword. The ballad is known in all the Nordic countries and closely related ballads were recorded in Scotland and in Brittany.10

Most of the poems in Gissur’s book are indeed ballads and most of those were recorded from Icelandic tradition. There are also, however, twelve poems translated directly from the Danish ballad edition of Vedel, which was first published in 1591 and reprinted several times in the seventeenth century. These twelve texts are close renderings of the Danish originals and distinct in style from the other ballads.

Along with the ballads, Gissur’s book contains four Eddic fairy-tales: Snjáskvæði (poem 24), Kötludraumur (poem 25), Þóruljóð (poem 48) and Kringilnefjukvæði (poem 49). Finally, there are twelve poems near the end of the book which are neither ballads nor Eddic fairy-tales. Jón Helgason considered one of those, Enska vísan, to be recorded from oral tradition while he judged the other eleven to have been composed pen in hand and transmitted through scribal tradition.11 The reader might be surprised by the frequent and confident statements made by Jón Helgason on which poems did or did not undergo oral transmission but there are many tell-tale signs which distinguish preservation by memory from preservation by ink.12

Gissur’s book does not mention any sources, authors or informants or provide any explanation on how the work was compiled. But the chance survival of some curious pages seems to offer a little bit of insight into Gissur’s methods. Three leaves which are now a part of G (probably originally as flyleaves) contain what seem to be working documents made by Gissur while he was compiling the poems.13 The notes contain the first few words of each stanza of Magna dans and Ásu dans — presumably Gissur made these notes in an effort to gather up all the stanzas and place them in the right order.

When these initial notes are compared with the final versions, it turns out that there are some differences. The final versions have more stanzas and some differences in wording, even if we only have a few words of each stanza for comparison. Presumably more stanzas came to light as Gissur continued working with his informants.14

Gissur wrote the extant G in 1665. It is his own copy of a previous version of his collection, known as *X. Another seventeenth-century collection of fornkvæði descended from *X is known as B (Add. 11.177). It contains most of the same poems as G but with a couple of omissions and a few additions. The hand in B is that of Oddur Jónsson (1648–1711), a relative of Gissur, also raised in the West Fjords.15 While B represents only a minor expansion of Gissur’s collection, a much more extensive expansion was to come.

The great collection

Magnús Jónsson digri (‘the stout’) of Vigur (1637–1702) in the West Fjords was an admirer of books and literature with enough worldly means to pursue his interests extensively. Along with his secretaries, Magnús produced a substantial collection of manuscripts, some of them of great size.16 The grandest of all is a hefty folio volume of the sagas of Icelanders (AM 426 fol.) with full-page colour illustrations of three saga heroes, including Egill Skalla-Grímsson.

Among many manuscripts of poetry produced under Magnús’s auspices was a collection of 186 fornkvæði produced in 1699–1700. The original manuscript, *V, is now lost but the text survives in good copies. This great collection begins with Gissur’s original collection and then expands it with more poems of the same sort — ballads translated from Danish as well as ballads and other poems recorded from Icelandic tradition.

The great collection contains two Eddic fairy-tales that are not in G — Vambarljóð (poem 176) and Gullkársljóð (poem 177). Both have clearly been through oral transmission but we can be sure that Gullkársljóð was not collected from memory or oral performance specifically for *V. An earlier text of Gullkársljóð exists in a manuscript (JS 28 fol.) written ca. 1660 for bishop Brynjólfur Sveinsson. The texts in 28 and *V are so similar — the same 71 strophes in the same order — that they are highly unlikely to represent two independent recordings from the sort of oral tradition that existed in seventeenth-century Iceland.

Since Vambarljóð and Gullkársljóð are adjacent in *V it seems plausible that they were obtained from the same source. We could speculate that Vambarljóð already existed in written form ca. 1660 like the four Eddic fairy-tales we have in Gissur Sveinsson’s hand and the one that we have in a manuscript written for his brother, Brynjólfur. Some support for this is found in the L version of Vambarljóð which is discussed later on.

A glimpse of the informants

While the seventeenth-century collectors of fornkvæði left us little information on their sources, the arrival of Árni Magnússon (1663–1730) on the scene clears away some of the fog. Eager to collect almost any information on the past, Árni did not neglect the value of texts and knowledge in human memory and in some cases the fornkvæði written down for Árni include information on the informants.

When Árni was in Álftanes in Iceland in 1703 he had a ballad recorded, Kvæði um sankti Hallvarð. The informant was a woman near the age of eighty.17 Another ballad, Eyvindar ríma, is also noted by Árni to have been recorded from an old woman.18

Árni seems to have made a particular effort to collect the Eddic fairy-tales. What survives of his collection in AM 154 8vo includes seven texts of Kötludraumur, four of Snjáskvæði, two of Kringilnefjukvæði and one each of Bryngerðarljóð, Hyndluljóð and Vambarljóð.19 One of the texts of Snjáskvæði was recorded from ‘a confused old lady who had learned it from her mother’.20 Árni also had a text of Vambarljóð (the Þ version) recorded from an old woman, as described below. The source of Bryngerðarljóð was Guðrún Hákonardóttir (1659–1745), who supplied Árni with many poems recorded from oral tradition.21

Judging from Árni’s informants, the fornkvæði tradition seems to have been kept alive by women and this is corroborated by two other sources. One is Landbúaljóð by Eiríkur Hallsson (1614–98) which mentions ‘the beautiful old fornkvæði of Norway which the old ladies would repeat in the dark.’22 Another source is a letter from Snæbjörn Pálsson (1677–1767) to Árni Magnússon written in 1708. Snæbjörn comments on a particular book of fornkvæði, probably the great collection:

It seems to me that the book of fornkvæði is not as rich in poems as I knew the hearts and minds of eighty-year-old women to be when I was a child. But most of them are buried in the ground now along with their knowledge.23

Although Snæbjörn may have seen his childhood in a nostalgic light, there are real reasons to believe that the fornkvæði tradition was already in decline by the early eighteenth century. The seventeenth-century collectors were able to obtain more poems and more complete poems than their later counterparts. One constant, however, is that the known informants are predominantly women in later times as well.24

The feminine leanings of the Icelandic fornkvæði tradition are clear not only from the gender of the known performers but also from the content of the poems themselves.25 This is true both of the ballads and the Eddic fairy-tales. Vambarljóð certainly fits this pattern. Both the hero and the antagonist are women and the purpose of the male characters is to serve as their love interests and family members.

The story: a summary of the V version

Some of the subsequent discussion will be easier to follow for readers that know the story of Vambarljóð and thus it may be convenient to have a summary at hand. The V version is complete enough to be summarized as a coherent story. Insofar as they are preserved, the J and Þ versions largely agree with V but differ in some details.

King Hringr and Queen Alþrúðr have a happy marriage and a promising daughter named Signý. The queen dies and the king is distraught, going every morning to her burial mound to grieve. Signý attempts to comfort him but he cannot be consoled and sends her away. She then predicts that the king will be betrayed and walks saddened back to her bower.

A woman named Yrsa arrives at the burial mound and introduces herself to king Hringr. He suspect she is a troll-woman (‘flagð’) and attempts to send her away but she shakes a drop of wine onto the king’s lip. He is then bewitched and under Yrsa’s control and takes her as his new queen. Yrsa envies Signý for her beauty and curses her to take the shape of a stomach. Signý compels Yrsa to include some way to undo the curse. Yrsa replies that if Signý gets married to a king’s son then Yrsa’s curses will be undone and she will die.

Signý, now in her stomach shape, rolls into a different land, ruled by one King Ásmundr with the assistance of his mother. She finds a peasant couple near the royal estate and convinces them to take her on as an adopted daughter and a hard worker. Signý then takes to driving the goat herd of the old couple onto the king’s field to have the goats graze there. King Ásmundr is away on an expedition but when he returns his men tell him that an old lady’s daughter has been grazing his fields and causing damage. The king is angered by this and goes alone to attend to the issue. He meets Signý, commands her to leave and then strikes her. As he strikes Signý, Ásmundr becomes stuck to her even as she begins rolling around. Distraught, he asks her what he should do in order to be released. Signý replies that he must propose to her and wed her as he would a princess. The king is forced to accept.

At home, Ásmundr’s mother asks him why he is unhappy. He asks her in turn for poison to drink. In the next scene, Signý the stomach rolls before the throne of the king and taunts him for his sadness. In the evening, the king’s mother puts Signý into bed with the king and they fall asleep together. As Signý wakes, she feels as if she is burning. She is now in human form and discovers that the king is burning her stomach form and asking her for her name. She tells him about the curse and asks him to bring her to her father. He proposes to her again and sends a messenger to her father, King Hringr. The messenger learns that Yrsa is dead and relays a message from Signý that her body should be burnt and the ashes thrown out to sea. Finally, Hringr sails to King Ásmundr’s realm and asks Signý to accept Ásmundr’s proposal. The tale ends happily.

The Eddic fairy-tales: love, elves and ogresses

In order to contextualize Vambarljóð, this section and the next briefly review the other seven Eddic fairy-tales. These poems have much in common, including themes, poetic language and in some cases even the names of the characters.

Going by the number of attestations, the most popular of the Eddic fairy-tales was Kötludraumur, ‘Katla’s dream’. It is also the only one to have a historical setting, tenth-century Iceland; the main characters are mentioned in Landnámabók. The title character, Katla, has a dream in which she is impregnated by an elf. She confesses this to her husband, Már, but he takes this kindly and they raise the child together. Gísli Sigurðsson takes Kötludraumur to deal with the social issue of extramarital pregnancy, which carried harsh penalties under Icelandic law after 1564. In his interpretation, the popularity of the poem suggests that the public had a more lenient attitude to such infractions than the law.26 In a response article, Einar G. Pétursson convincingly argues that the composition of the poem must predate the Reformation. He offers various additional considerations on Icelandic attitudes to infidelity and the reality of elves.27

Another fairy-tale of human-elf relations is Gullkársljóð. The princess Æsa falls in love with an elf named Gullkár. Her parents disapprove of the relationship but she eventually follows her lover to Álfheimar. The poem has many plot points in common with Yonec by Marie de France, which was translated to Norse in the thirteenth century.28 I have previously pointed out similarities between Gullkársljóð and the Eddic poem Vǫlundarkviða, both in themes and in turns of phrase.29 The Eddic fairy-tale Bryngerðarljóð also has much in common with Gullkársljóð, including a love-affair opposed by parents.

Þóruljóð tells the puzzling story of a tall woman or ogress, Þóra, who comes visiting at a farm in pre-Christian Denmark during a Yule feast.30 She is welcomed by the young host, Þorkell, despite the reservations of his mother. Þóra eventually rewards Þorkell by giving him a sail with some favorable properties. In a previous article, I pointed out similarities between the Þóra of the poem and the Háa-Þóra (‘Tall Þóra’) of an Icelandic game referred to in sources from the seventeenth to the nineteenth centuries.31 From the point of view of metrics and historical linguistics, Þóruljóð is the most archaic of the Eddic fairy-tales. It is possible that it is genuinely older than the others but another possibility is that it is merely better preserved. Þóruljóð is the shortest poem, only 26 stanzas, and short poems may get through centuries of oral preservation with fewer changes than longer ones.

Kringilnefjukvæði is another short poem with a helpful ogress, Kringilnefja. She joins the household of a poor widower and his daughter, Gullinhöfða. The ogress educates her stepdaughter in needlework and helps her in a rather forceful way to marry a prince. In the end it turns out that the stepmother ogress was Gullinhöfða’s aunt under a curse.

The evil stepmother poems

While Kringilnefjukvæði has a helpful stepmother, the more common trope of an evil stepmother cursing her stepdaughter occurs in three Eddic fairy-tales. Snjáskvæði combines this theme with an interest in elves and tells the story of an elven princess who is cursed to appear as a human king. As pointed out by Lee Colwill, the transformation seems to take place chiefly through the taking on of some external trappings of masculinity:

Réð ég kvenglysi að kasta mínu.

Steyptu seggir yfir mig svalri brynju.

Settu skreyttan hjálm á skarar fjall

en í hendi hjaltorm búinn.32

I cast off my female finery. The men threw a cool mailcoat over me. They placed an ornamented helmet on my hair mountain [head] and a decorated hilt-worm [sword] in my hand.

Hyndluljóð is the Eddic fairy-tale which is most similar to Vambarljóð. Princess Signý Logadóttir is cursed by her stepmother to take the form of a bitch (‘Hyndla’), an enchantment to be lifted only by marriage to a prince. Signý curses her stepmother in turn to take the form of a cat. Hyndla succeeds in befriending a peasant couple and takes to driving their cattle. A neighboring prince, Ásmundr, encounters Signý for a brief moment when she is in human form. He falls in love with her; they marry, and during the wedding night Signý permanently reverts to human form.

Hyndluljóð shares most of its plot points and even the names of the protagonists with Vambarljóð. One interesting difference is that the relationship between the princess and her suitor is never antagonistic in Hyndluljóð. Einar Ól. Sveinsson believed that Hyndluljóð was derivative of Vambarljóð.33 If true, it might explain that the episode with the peasant couple is integral to the story in Vambarljóð but seems to serve no particular purpose in Hyndluljóð. On the other hand, it seems natural that a bitch would drive livestock around and it is less expected that a stomach would do so.

There is a prose narrative with significant similarities to Vambarljóð and Hyndluljóð in Hrólfs saga kraka. The relevant section is worth quoting in full:

Einn jöla aptan er þess gietid ad Helgi k(ongur) er kominn j reckiu og var vedur jllt vte, ad komid var vid hurdina og helldur ömätuliga. Honum kom nu j hug ad þad væri ökongligt ad hann lieti þad vte sem vesallt var, enn hann mꜳ̋ biarga þui. Fer nu og lykur vpp dyrunum. Hann sier ad þar er komid eitthuad fätækt og tǫtrugt. Þad m(ælir), vel hefur þu nu giǫrt k(ongur), og fer sijdan jnn j skiemmuna. K(ongur) m(ælir), ber ꜳ̋ þig halm og biarnfelldi so þig kali ei. Þad m(ælir), veittu mier reckiu þijna herra og vil eg hiä þier huÿla, þui lÿf m(itt) er j vedi. K(ongur) s(eigir), rijs mier hugur vid þier, enn ef so er sem þu s(eigir), þä ligdu hier vid stockinn, j klædum þijnum og mun mig ecki saka. Hun giǫrir nu so. Kongur snijr sier fra henni. Liös brann j husinu og er stund leid, leit hann vm ǫxl til hennar. Þä sier hann ad þar huÿlir kona so væn ad eij þikist hann adra konu frydari sied hafa. Hun var j silcki kyrtli. Hann snijr sier þä skiött ad henni med blydu. Hun m(ælir), nu vil eg fara j burt s(eigir) hun, og hefur þu leist mig vr micklum naudum, þui þetta var mier stiupmodur skǫp, og hef eg marga konga heimsockta, enda legdu nu ei med lytum.34

One Yule evening King Helgi had gone to bed and there was bad weather outside. There came a knock at the door, a rather weak one. It occurred to him that it would not be kingly to have whatever wretch this was remain outside if he could help it. He goes and opens the door. He sees that something poor and tattered has arrived. It speaks: ‘You have done well, king’, and then enters the hall. The king says: ‘Take some straw and bear hides so that you do not freeze.’ It says: ‘Grant me your bed, lord, and I want to rest with you, for my life is at stake.’ The king says: ‘I shudder at you but if it is as you say then lie here at the side of my bed in your clothes and that will do me no harm.’ She now does that. The king turns away from her. A light was burning in the house and when some time had passed he looked over his shoulder at her. Then he sees that a woman is resting there, so beautiful that he feels he has never seen a prettier woman. She was wearing a robe of silk. He now turns to her quickly but gently. She speaks: ‘Now I wish to go away’, she says, ‘and you have released me from great distress for this was a stepmother’s curse and I have visited many kings and do not blame me for it’.

This episode has much in common with the Eddic fairy-tales. The story begins the same way as in Þóruljóð, with a strange woman knocking on the door during Yuletide. As in Hyndluljóð and Vambarljóð, a woman is cursed into some wretched shape by her stepmother and the curse is lifted in a prince’s bed. The woman, furthermore, is an elf.

Hrólfs saga kraka was likely composed in the fourteenth century, but stepmother curses are also referred to in earlier sources. The early thirteenth-century Sverris saga refers to ‘old stories in which it is said that the children of kings were the victims of stepmother curses’.35 There is also a reference to stepmothers in Óláfs saga Tryggvasonar by Oddr Snorrason: the saga tells of ‘stepmother stories told by herdsmen, the truth of which is known by none and that always make the king out to be the least in their tales’.36 Vambarljóð is certainly a stepmother story with humiliating roles for the kings involved. It belongs to a genre current in medieval times and, as shown in the two following sections, the preserved texts have stylistic traits characteristic of medieval poetry.

Poetic formulas

It is immediately apparent that Vambarljóð uses a great amount of traditional poetic language, formulas, kennings and poetic words. We can take the first stanza of the Þ version as an example:

Þ-1. Fardu heim hedan heillin góda

hafdu þỏck fyrer þína gaungu

mey veit ek ỏngva ne mans konu

sem bỏlstỏfunum bregde mínum.

Go home from here, dearest. Thank you for your visit. I know no maiden nor man’s wife who might alter my baleful staves.

The formula in short lines 5–6, mey né manns konu, also occurs in the Eddic poems Hávamál, Lokasenna and Sigrdrífumál. The last two short lines are also highly reminiscent of Sigrdrífumál, which has bǫlstǫfum in strophe 30 and bregða blundstǫfum in strophe 2.37 Short lines 2–3 have a parallel in Kötludraumur 18, ‘Hún þakkaði mér / mína gaungu’.38 Short lines 1–2 have a parallel in Vambarljóð V-29, even though the context there is quite different. In sum, every part of this strophe is built out of poetic words and phrases that occur elsewhere.

In previous work I identified and listed a number of poetic formulas occurring in Vambarljóð. I defined ‘poetic formula’ as ‘a combination of words found at least twice in texts using a poetic register but not elsewhere’.39 Under this definition I came up with forty-seven poetic formulas, of which twenty-seven were shared with other Eddic fairy-tales and seventeen with the poems of the Codex Regius. A smaller number were shared with other poems in fornyrðislag, with skaldic poetry or with rímur cycles.

Dating Vambarljóð

In previous work on Eddic fairy-tales I have pointed out some linguistic and metrical traits that are indicative of medieval origin. In the following, I look at these features in the three texts of Vambarljóð edited here (V, Þ, J) and also in the long version (L) as printed by Ólafur Davíðsson.

The medieval features in question are instances of alliteration between j and vowels40 as well as alliteration between sl or sn and s.41 The A2k metrical type is a further archaic trait.42 It was a staple of medieval alliterative poetry but after the Reformation it appears mostly to occur by accident. Finally, I count instances where the Vambarljóð texts share a poetic formula with the poems of the Codex Regius.43 The results are shown in Table 1.

| Eddic formulas | A2k verses | S-alliteration | J-alliteration | Total | Strophes | Total per 100 strophes | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| V version | 17 | 13 | 1 | 2 | 33 | 62 | 53 |

| J version | 7 | 8 | 0 | 2 | 17 | 39.75 | 43 |

| Þ version | 2 | 4 | 1 | 0 | 7 | 27 | 26 |

| L version | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 2 | 80 | 3 |

The table indicates that the L text has essentially no identifiable medieval traits. The V text, however, has the most medieval appearance. As it turns out, there is a difference between the first and the second half of the V text in this respect, as shown in table 2. The first half has significantly more medieval traits.

| Eddic formulas | A2k verses | S-alliteration | J-alliteration | Total | Strophes | Total per 100 strophes | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| V (1–31) | 12 | 9 | 1 | 2 | 24 | 31 | 77 |

| V (32–62) | 6 | 4 | 0 | 0 | 10 | 31 | 32 |

An alternative way to proceed is to look at late or post-medieval traits and again I have selected four. One is the presence of the suffixed article, which is mostly avoided in medieval fornyrðislag poetry. All four Vambarljóð texts have a number of instances.44 A less common late trait is to begin a sentence with a preposition, which is a violation of Kuhn’s second law and abnormal in medieval fornyrðislag.45 Another syntactic trait which is late in this context is to place the verb further than the second position into an unbound sentence.46 Finally, I have counted the number of verses where a svarabhakti vowel is needed for the number of syllables to rise to the normal minimum of four.47 This phenomenon entered Icelandic poetry in the fourteenth century and meant that previously monosyllabic words like hendr could occur as disyllabic hendur.48

| Suffixed article | K2 violations | K4 violations | Svarabhakti vowel | Total | Strophes | Total per 100 strophes | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| V version | 13 | 0 | 3 | 8 | 24 | 62 | 39 |

| J version | 28 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 34 | 39.75 | 86 |

| Þ version | 18 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 20 | 27 | 74 |

| L version | 34 | 12 | 20 | 30 | 96 | 80 | 120 |

Again the L version has by far the latest appearance while V has the earliest. And again it is true that there is a striking difference between the first and second half of the V text, as shown in table 4.

| Suffixed article | K2 violations | K4 violations | Svarabhakti vowel | Total | Strophes | Total per 100 strophes | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| V (1–31) | 3 | 0 | 2 | 3 | 8 | 31 | 26 |

| V (32–62) | 10 | 0 | 1 | 5 | 1> | 31 | 52 |

It is tempting to conclude that V has a more archaic appearance than J and Þ because it is better preserved and thus closer to the medieval text that these three versions are derived from. Perhaps it is also true that the first half of V is better preserved than the second half: this would be a natural enough state of affairs for a text preserved in human memory.

While linguistic and stylistic traits show that Vambarljóð must have existed already in medieval times it is difficult to further narrow down the time of origin. Ideally we would like to make comparisons with poetry in fornyrðislag but there is little after the thirteenth century which can be precisely dated. The most plausible candidate for a comparison is Skaufalabálkur, which there are good reasons to date to the mid-fifteenth century.49 The linguistic dating traits of that text are similar to the V, Þ and J versions of Vambarljóð. On the other hand, Skaufalabálkur has no identifiable Eddic formulas. The poetic language of Vambarljóð and the other Eddic fairy-tales gives us some reason to think these poems may have earlier origins. I would not like to rule out composition in the thirteenth century or even earlier in which case most or all of the late traits would have accumulated during the oral transmission. Further studies on this corpus as a whole may shed more light on the question.

The three versions of Vambarljóð

The V version

A version of Vambarljóð was preserved in the manuscript *V, a large collection of ballads and other popular poems written for the magnate Magnús Jónsson at Vigur in 1699–1700. This book is now lost but two copies of it survive. One is V1 (NKS 1141 fol.), made in Copenhagen in the eighteenth century. The other is V2 (JS 405 4to), made in Iceland in 1819.50 These are both good and faithful copies with minimal editorial interventions and relatively few mistakes. Vambarljóð in particular is also preserved in two other manuscripts derived from *V. One is T (Thott 489 8vo, eighteenth century) which is chiefly derived from *V but with some stanzas and readings from the J version as well as some intentional editing. Finally there is I (JS 80 8vo, ca. 1800), which is clearly derived from *V but with a significant amount of editing.51

This edition uses V1 as its base text but in cases where the combined evidence of V2, T and I indicates that *V had another reading I have emended the base text accordingly. The resulting edition should closely resemble the text of the lost manuscript *V. The apparatus gives every variant reading from V2 but does not include the many isolated readings from T or I in order not to overload the apparatus with secondary variants. Jón Sigurðsson (1811–79) made a copy of V1 in JS 406 4to. He suggests some reasonable conjectures which I have cited in the apparatus.

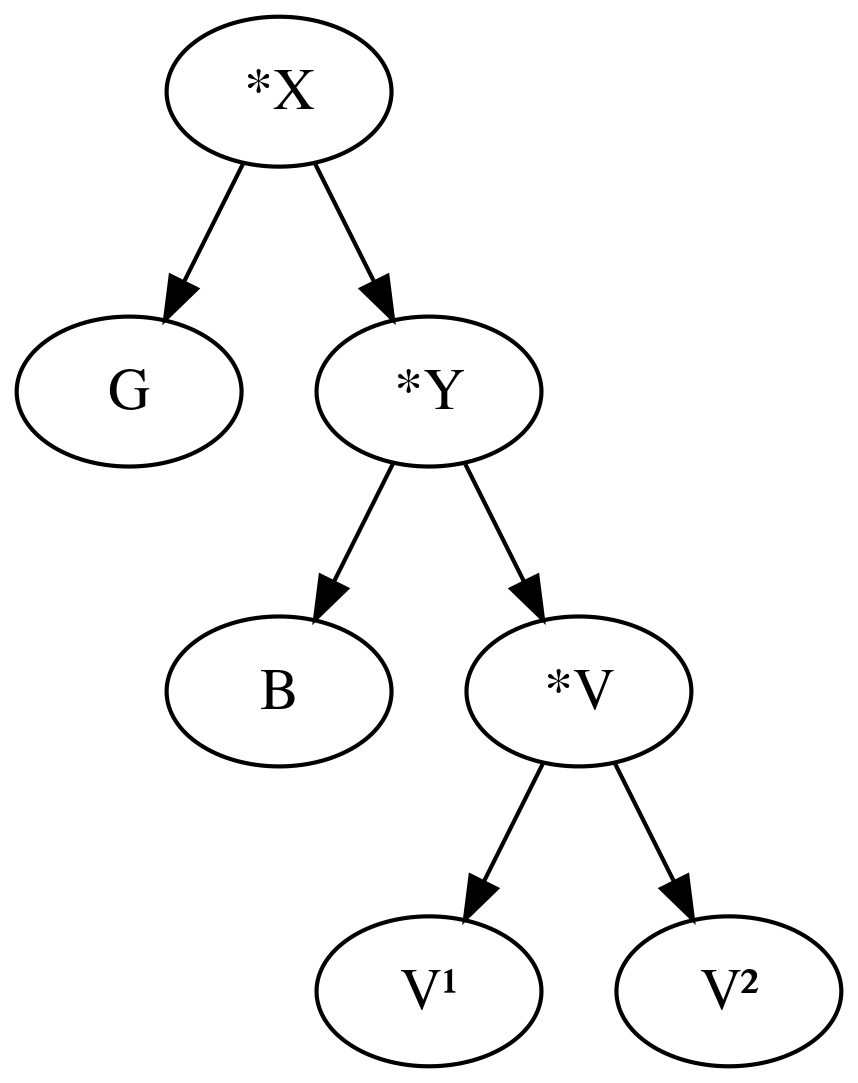

Some texts preserved in *V are also preserved in older manuscripts related through a scribal tradition. In those cases it is sometimes apparent that the editors of *V tried to improve on the text from a metrical point of view.52 A case in point is Þóruljóð, which was found in *V but also in the manuscripts G (AM 147 8vo) and B (Add. 11.177). The relationship between these mansucripts was investigated by Jón Helgason and is shown by the stemma in figure 1.53

Figure 1. Jón Helgason’s stemma of several Icelandic folk poetry collections

The text of the final stanza of Þóruljóð is as follows in G:

Þu muntt sigla framm j romu

vera fremstur j før allra manna

skal þig alldrei hamingjuna skortta

ä medann su hin bjartta byrvod þoler.54

The first three verse pairs of this stanza have a structural defect — the verse pairs are not linked by alliteration. The text in B is nearly identical and no better in terms of alliteration so the exemplar of *V must have had the stanza in this form as well. However, the editor of the *V text (presumably Magnús Ketilsson, the scribe of the manuscript) took it upon himself to remedy these alliterative problems. The text in V1 is as follows (V2 differs only in orthography):

Þú munt sigla seggr í rómu

og vera fremstr í fǫr flestra manna

hal skal alldri hamingiu skorta

á medan sú hin bjartta byrvoð þolir.55

The insertion of some handy words has brought the alliteration into order for all three verse pairs. The meaning of the strophe is minimally affected. The editor of the V text does not seem to compose new stanzas or radically alter the sense of the text.

Has the text of Vambarljóð in the V manuscripts been edited in a way similar to that of Þóruljóð? Perhaps. In some cases where we have comparative material in J or Þ we might suspect similar editing. Here is one example:

J-4.5-6 mei skalltu verda i vambarlike

V-19.5-6 víf skalltu hafa vambarlíki

It is possible that the editor of the V text inserted the synonym víf for mey to get alliteration between the verse pair. If it was a conjecture it might be a successful one — the original text may have had víf.

The objective of the V collectors was to compile a book of enjoyable poetry — ‘til gamans, skemtunar og Dægra-styttingar’ as the title page proclaimed.56 A little polishing of the text is in accordance with that objective. But any such editing of Vambarljóð must have been carried out opportunistically rather than systematically since the V text has a number of verse pairs with unsatisfactory alliteration. Indeed, the first verse pairs in stanzas 30, 31, 50 and 54 in V have no alliteration at all.

The Þ version

The Þ version of Vambarljóð was recorded from oral tradition for Árni Magnússon. The informant was Þorbjörg Guðmundsdóttir (b. 1636, d. after 1703) and on the basis of her name I refer to this text as the Þ version. Þorbjörg’s first known residence is Stapar in Vatnsnes but her family later relocated to Snæfellsnes where she lived first at Arnarstapi and then at Hellnar.57 These locations are at some distance to Vigur and Eyri, where the V and J versions were recorded.

Figure 2: Locations in Iceland relevant to the recording of Vambarljóð; V was recorded at Vigur, J probably at Eyri. Stapar, Hellnar and Arnarstapi are locations where Þorbjörg Guðmundsdóttir, the source of Þ, is known to have lived.

Þorbjörg was the mother of Guðmundur Bergþórsson, a prolific poet. An eighteenth-century biography of Guðmundur briefly mentions his mother. She seems to have had a warm relationship with her son and to have enjoyed his poetry. An illness at the age of four left Guðmundur largely paralyzed but his left hand was hale and he could use it not only to write but also to crawl at surprising speed while dressed in leather pants.58 This must have been an unusual sight and one wonders if Guðmundur heard Vambarljóð from his mother and if he felt any kinship with Signý, the cursed princess who rolled around instead of walking.

When Jón Ólafsson of Grunnavík (1705–79) made the first catalogue of the Arnamagnæan manuscript collection (AM 477 fol.) three versions of Vambarljóð were preserved under the shelfmark AM 154 8vo. Two of these texts must have been lost since only one version of Vambarljóð remains in 154 — the L version. The L text was copied from 154 to NKS 1894 4to by Markús Magnússon (1748–1825). Following this, Markús copied out another version, the Þ text, which was presumably also taken from 154. The page preceding the poem itself has this piece of information: ‘Scriba ad A. Magnæum: Ad eg síne ydr þó nockurn lit, er þetta fragment Vambarlióda sem afgỏmul kelling móder Gudmundar Bergþórssonar kunne’ (‘Written to Árni Magnússon: In order to make some effort on your behalf, here is a fragment of Vambarljóð as a very old woman knew it, the mother of Guðmundur Bergþórsson’). This must be taken from a letter written to Árni Magnússon which is not otherwise preserved. Presumably, Árni had written to one of his friends in Iceland, requesting Vambarljóð and perhaps other texts or information as well. The apologetic wording (‘þó nockurn lit’) indicates that the correspondent was only partially able to fulfill Árni’s requests. He or she is well aware that the Vambarljóð text is incomplete, a ‘fragment’, and presumably Þorbjörg thought so as well. A brief prose introduction corresponds to the opening stanzas of the other versions.

While the collectors of the seventeenth century were searching for complete poems with entertainment value, it is characteristic of Árni’s philological interests also to have collected any available scraps, no matter how imperfect. While we do not have the letters he wrote seeking Vambarljóð we can guess at their contents from enquiries that have survived. Especially interesting is a letter written by Árni to Ólafur Einarsson on December 10, 1707:

Kona hefur heited Ragnhilldur Þorvardz dotter su er kunne Modars rimur, tvær ad visu, dötter Ragnhilldar skal heita Vigdis Þorlaks dötter, og vera j vist ä Þyckva bæjar klaustre. Væri nu svo ad þessi Vigdis lifdi, og j ỏdru lage kynne sagdar Modars rimur, þa vil eg ydur umbeded hafa, ad läta epter henne uppskrifa nefndar rimur, eda svo mikid sem hun ur þeim kann. En kunni hun eckj samfleytt j rimunum, þä bid eg ad epter henne mætte uppteiknast skilmerkeliga efned ur þeim, og þar jafnframt þau einstỏku erenden er hun kann ur rimunum hier edur þar.59

A woman named Ragnhildur Þorvarðsdóttir knew Móðars rímur, two in number. Ragnhildur’s daughter is thought to be named Vigdís Þorláksdóttir and to be a part of the household at Þykkvabæjarklaustur. In the case that this Vigdís is alive and, secondly, does know these aforementioned Móðars rímur, I would like to ask you to have the aforementioned rímur recorded from her, or as much as she knows of them. But if she does not know the rímur contiguously then I would ask that the storyline from them should be carefully recorded as well as the individual stanzas she knows from here or there in the rímur.

As it happened, Vigdís did know Móðars rímur from beginning to end and they have come down to us only by virtue of being recorded from her knowledge. But it is worth considering Árni’s comment on the eventuality that the informant might not know the whole text but might know parts of it and be able to summarize the storyline. Whoever recorded the Þ version of Vambarljóð might have received similar instructions and the brief prose introduction to the poem might be an attempt to honour them. The Codex Regius of the Eddic poems also has prose introductions to some of its poems as well as prose connecting stanzas or groups of stanzas within poems. In some cases the explanation might be, as in the case of the Þ text, that parts of the poems had been forgotten.

In addition to NKS 1894 4to, there is another manuscript which may or may not have some textual value. This is JS 430 4to, which was in the possession of Hallgrímur Scheving (1781–1861). There is a copy here of the Þ text but I have been unable to determine whether it is copied from NKS 1894 4to or directly from the lost text in AM 154 8vo. In any case, it is clearly a less accurate copy than 1894, with many conjectural emendations. In the edition here, I have selectively cited variants from 430 when they seemed plausible and not obviously the result of conscious editing. There are copies of the 430 text in JS 581 4to and Lbs 202 8vo.

The J version

The J text has been preserved in a rather curious way on two individual leaves of paper that are now in different collections but must have originally belonged together. One is in the Icelandic National Library under the shelfmark JS 406 4to, a collection of material from Jón Sigurðsson (1811–79). The leaf has two texts written in a hand dating to ca. 1700 or the early eighteenth-century. One text is Vambarljóð while the other is Þornaldarþula, a bizarre folk poem of the þula type.60 The leaf gives no indication to the provenance of the texts. The abbreviation ‘def.’ between some strophes in Vambarljóð correctly indicates that the text is defective — some strophes have been forgotten.

The other source of the J text is a single leaf at the back of Thott 489 8vo which I refer to here as J*. Kaalund’s catalogue indicates that the leaf was used as a cover for 489 at that time but at some point it must have been inserted and glued into the manuscript.61 This leaf is originally an envelope for a letter addressed to Jón Sigurðsson (1702–57), provost (prófastur) at Eyri by Skutulsfjörður. The envelope was reused for some notes and texts, including Kötludraumur and some nine strophes or half-strophes of Vambarljóð.

Several facts make it clear that J and J* belong together. They are written in the same hand and both use the abbreviation ‘def.’ to indicate missing material. Furthermore, there is no overlap in the strophes recorded in each of them. It seems apparent that J was written first and represents someone’s attempt to get through Vambarljóð from beginning to end with the strophes in a coherent order while realizing that some were missing. Then J* constitutes a partially successful effort to recover some of the missing material from memory. The strophes in J* are not in the order of the narrative but presumably in the order in which they came to mind. It is interesting that the name Yrsa occurs nowhere in the original J recording but it occurs in each of the first strophes of the J* text. Presumably the name came to mind and with it some disjoint text fragments containing it.

I assume that the writer of J and J* was provost Jón Sigurðsson, principally because no-one else would be likely to reuse as scrap paper an envelope addressed to him. I have loosely compared the handwriting in J and J* to some of the many preserved manuscripts written by Jón and there seem to be enough similarities for the theory to hold. There is, however, substantial variation in Jón’s handwriting depending on what sort of text he is writing and in what sort of context — doubtless there are also chronological developments. A detailed study of his oeuvre would be required to firmly confirm that J and J* were written by him.62

Jón Sigurðsson grew up with Jón Ólafsson, who became Árni Magnússon’s assistant and a prolific scholar. Both Jón Sigurðsson and Jón Ólafsson came to Copenhagen as students in 1726. Jón Sigurðsson graduated in 1729 and then returned to Iceland. He became a pastor at Eyri in 1730 and a provost in 1732. In 1741 he returned to Copenhagen to work as a scholar.63 Since J* is originally an envelope addressed to Jón as provost it must be from a letter written between 1732 and 1741. It seems likely that the piece of paper was reused for notes on poetry shortly after being received, presumably while Jón was still at Eyri in Iceland — a short distance from Vigur where the great collection (*V) was created. Most likely, Jón then brought J* (and J) with him to Copenhagen in 1741. While Jón was a student in Copenhagen in 1726–29 he had got to know Árni Magnússon and this may have inspired him to write down Vambarljóð and Þornaldarþula at a later date in Iceland. Most likely this was from some unknown informant though it is not inconceivable that he was writing from his own memory.

The J text was used by the compiler of Thott 489 8vo (perhaps Jón Sigurðsson) to make a neatly written and edited version of Vambarljóð. The original intention seems to have been to produce a text based on J and J* but after writing out the first three stanzas from J, the compiler must have discovered that it was difficult to construct a complete narrative out of the J text. He then started anew, this time with the V text as the base. Many readings from J and J* are, however, introduced along with some stanzas which are only found in J. The result is that Thott 489 8vo (T) contains a new composite text type, longer than the source versions. Ólafur Davíðsson’s edition of Vambarljóð uses T as one of its sources and includes the strophes which T had sourced from J.

Jón Þorkelsson indicates that there is a text of the J type in JS 398 4to but I have been unable to find any trace of Vambarljóð in 398.64 Possibly, Jón had confused JS 398 4to with JS 406 4to, possibly there was a text in 398 that has now been lost, or possibly the leaf in question was at some point moved from 398 to 406.

Among Jón Helgason’s documents preserved in Copenhagen is a transcript of JS 406 4to. I have cited some readings from this transcript as JH in the apparatus.

A comparison of V, J and Þ

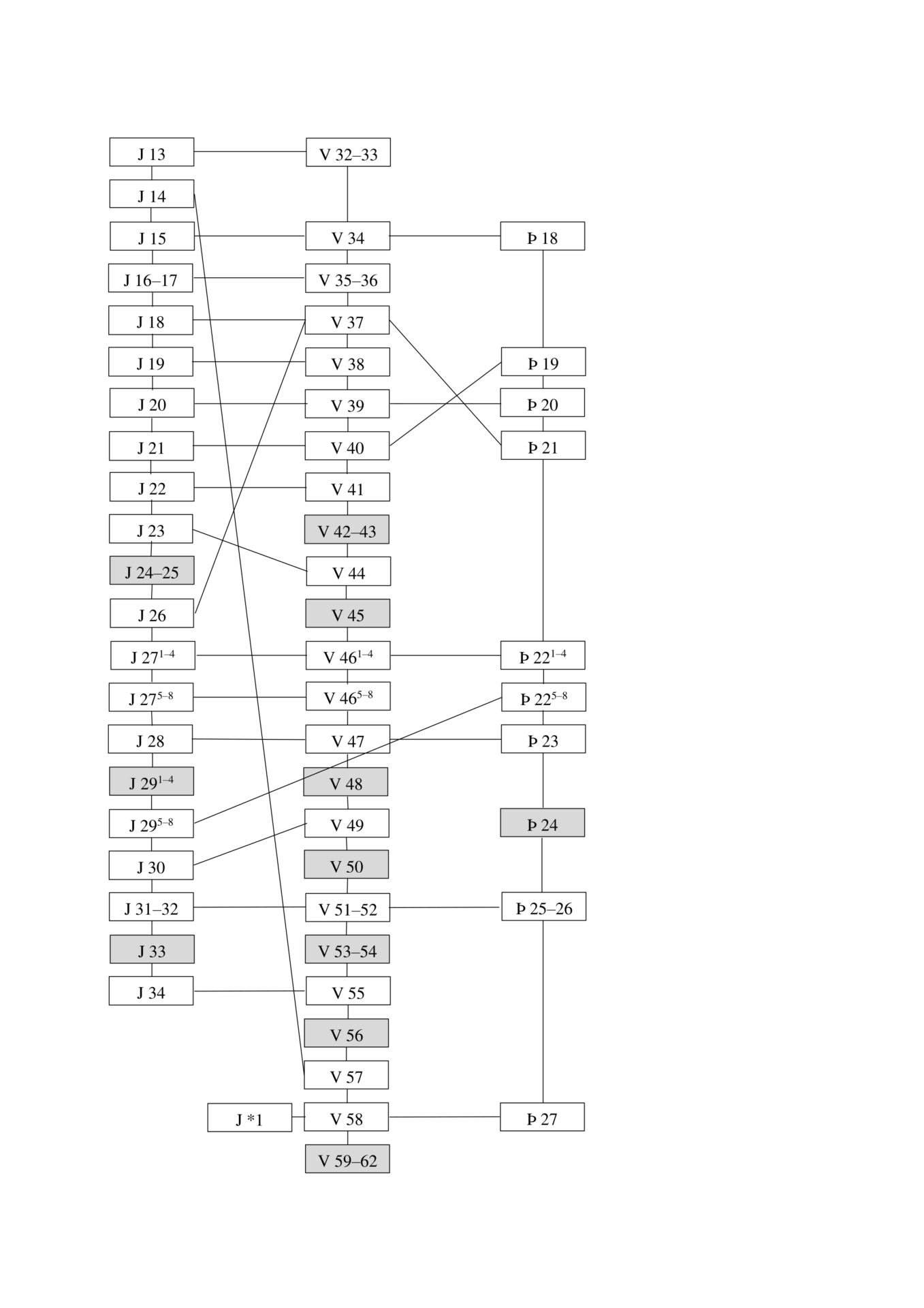

The three versions printed here have many corresponding strophes but each of them also has some material not shared by the others. A slightly simplified visualization of the relationship between the strophes of each version can be seen in figures 3 and 4. The overall picture is consistent with the idea that all three versions are derived from an oral archetype that was similar in scope to the V text. It seems especially telling that there is very little material common to J and Þ and lacking in V — chiefly the second half of J 29 / Þ 22.

I have compared the 16 stanzas that are, in whole or in part, shared by V, J and Þ. There is no clear pattern of common errors though it is tempting to think that J 32.4 til ats buenn is the original wording. The humorous point that the stomach is not being roasted for eating seems fitting while the vague wording in V and Þ might be a common error.

Many of the strophes found only in one preserved version may have been a part of the archetype while some may be new compositions to replace forgotten or half-forgotten lines. A third possibility is that some strophes might have migrated from other poems. This might be true for J 6, which has a close analogue in Hyndluljóð 4665 and which there is no trace of in V and Þ even though the surrounding stanzas are common to all of V, J and Þ. Another possible migrant is the sequence J 11.5–12.8, which mentions hafskrímsl ‘sea monster’ and the ‘vatni ausa’ ceremony, both of which are otherwise absent from the text. To be sure, it is not impossible to make some sense of this — a wandering stomach might look like some sort of marine creature. But it also seems possible that these lines come from a lost fairy-tale where a girl is cursed to appear as a sea monster.

I do think it would be possible to reconstruct a text moderately closer to the original composition — or to the oral archetype — by using the V text as a basis and then adding to it and correcting it in a few places based on the testimony of J and Þ. I have not done so here to avoid adding further complexity to what is already a lengthy treatment but it would be a worthwhile avenue for further study.66

Figure 3: Corresponding strophes in the first half of ‘Vambarljóð’; shaded strophes are unique.

Figure 4: Corresponding strophes in the second half of ‘Vambarljóð’; shaded strophes are unique.

Textual difficulties

There are two textual difficulties in Vambarljóð which I have not been able to resolve. The first is an obscure noun phrase which appears in three versions, all incomprehensible, in the three texts of the poem:

ef eg skal eiga ýr við grímu

þau hafa fádæmin flestu vm ollað. (V-45, 5–8)

If I shall have ýr við grímu it is mostly caused by abnormal events.

og so til blidrar brullaupid bua

þo hann ætle þig arfa grimu. (J-7, 5–8)

and celebrate the wedding with the sweet one though he think you arfa grimu.

so til blídrar brullaup drecka

sem hann ætte Ilfa grímu. (Þ-8, 5-8)

and celebrate a wedding with the sweet one as if he had Ilfa grímu.

The context in the Þ text could imply that the phrase refers to something positive but the context in the J version calls for a negative sense and the V version also seems to suggest as much. The word gríma can mean ‘night’ or ‘mask’ but the word also occurs as a troll-woman’s name. The form arfa could be accusative of arfi (‘heir’) so arfa grímu could formally mean ‘heir of the night’. While this sounds promising in English as a vague reference to an awful creature, I am not aware of any parallels in Old Norse. According to the Prose Edda, the mythological being Nótt (‘Night’) has three offspring, Auðr (‘Wealth’), Jǫrð (‘Earth’) and Dagr (‘Day’), but this does not seem to lead anywhere. The word ýr would typically mean ‘yew’ or ‘bow’ but neither sense seems to fit here. What Ilfa might be is no less obscure; ylfa is a rare word for she-wolf but this does not seem to help. It appears likely that ýr við, arfa and Ilfa are three corruptions of some lost word that had become incomprehensible to the transmitters of the poem.

These difficult verses have a further parallel in Egill Skallagrímsson’s Sonatorrek, which is only preserved in seventeenth-century copies:

maka eg upp ï aröar grimu

rïnis rejd rjette hallda67

I cannot uphold the rïnis wagon ï aröar grimu, rjette.

This, too, is very obscure and almost certainly corrupt. Even allowing for some conjectural emendations, there is no convincing interpretation of ïaröar grimu. I have no solution and will offer none.

The second textual problem occurs when the stomach is roasted:

nú mun elldzlitnum ǫllum linna

ef hilmi segir hvað þitt er heiti. (V-52.5–8)

All the colour of fire will end if you tell the prince what your name is.

hier mun ollum elldslitrum linna

enn siklinge segdu hvad þu heiter. (J-32.5–8)

Now all the elldslitrum will come to an end. Tell the prince your name.

While elds-litr (‘the colour of fire’) is a normal enough word it is surprising in this context. The word in the J version seems to be eld-slitr, a hapax legomenon seemingly meaning ‘the shreds of fire’, no less surprising in the context. There is a parallel to this half-strophe in Kringilnefjukvæði:

Nú mun álögum öllum linna,

en eg heiti Hildifríður.68

Now all the enchantment will come to an end and my name is Hildifríður.

The word álögum fits very well here semantically and we might consider if elldzlitnum/elldslitrum could have a similar meaning. There is a possible parallel in the word eluist, which occurs at the beginning of Guta saga and seems to mean ‘bewitched’.69 The word has been related to Old English ælwihta, ‘strange creatures’ and English eldritch with the first element, æl- or el-, meaning ‘foreign, strange; from elsewhere’.70 On the other hand, ælwihta has been related to the Eddic word alvitr, with initial a rather than e,71 though Sophus Bugge suggested a reconstructed *elvitr.72 Conceivably, Old Norse had *el-litr or *els-litr for ‘enchanted form’, which was then eventually reinterpreted as eldslitr.

The later texts

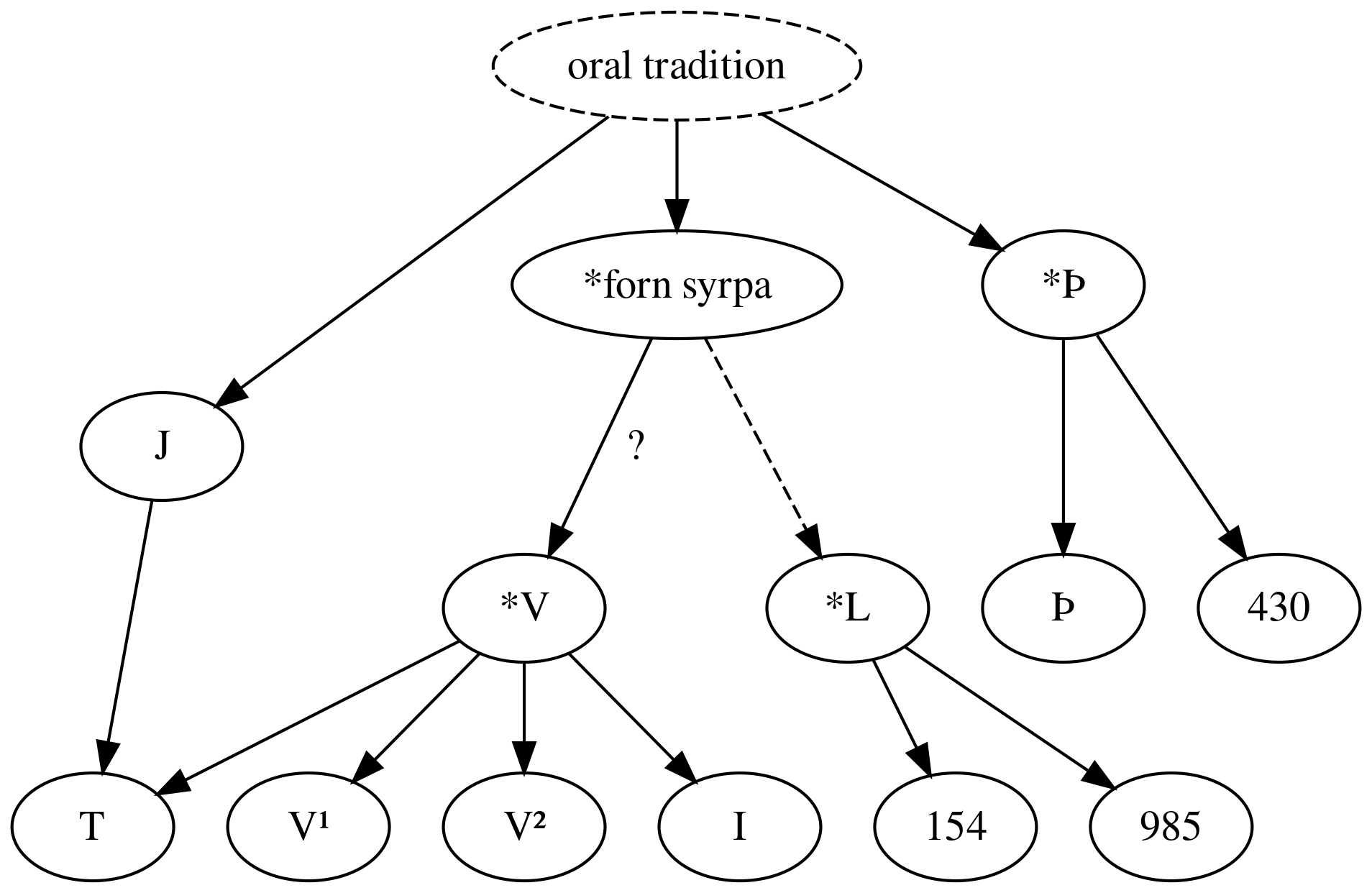

There are four texts which tell the tale of Signý Hringsdóttir which I have not edited here. First there is the L version of Vambarljóð, which is preserved in AM 154 8vo (early eighteenth century) and in Lbs 985 4to (mid-eighteenth century). Both manuscripts are defective: 154 ends with stanza 80 while 154 ends with stanza 123.73 Ólafur Davíðsson was unaware of 985 but he printed the text of 154 in his edition, which I use in the following citations.

The first three stanzas of the text provide an introduction in which the authorial voice says that in his or her youth they learned much from old books (‘á fornum bókum’) and that they found this adventure (‘ævintýri’) in an old collection (‘í einni fornri syrpu’). There is nothing implausible about this and perhaps the author did read a version of Vambarljóð in an old book, perhaps a fornkvæði collection from the 1660s that has not come down to us. The author may have remembered the storyline but little from the poem itself and thus arrived at the solution of composing a new poem.

The story of the L version is close to that of V, Þ and J but it has various additional details — for example Alþrúður is said to be from Hungary while Yrsa claims to be from Hálogaland. The text itself is very different from the older versions but a few stanzas have some recognizable verbal similarity. The closest similarity is in stanza 54, which has ‘sem úr nýdrepnu / nauti væri’, a phrase which is also found verbatim in V 27, J 8 and Þ 12. There is a similar case in strophe 42:

Þig æði ormar stinga,

grös og steingur, grund og skógar,

nema þú leggir mér líkn með nokkra,

svo eg ósköpum úr megi komast.74

You will be maddened, snakes will sting you, grass and rods, ground and forest, if you do not grant me some mercy along with this so that I can escape the enchantment.

Short lines 5–6 here have a closely corresponding text in stanzas V 20, J 5 and Þ 7. These two shared quarter strophes seem to suggest that the author of the L version had at some point read or heard a version of the older poem.

According to Rithöfundatal by Hallgrímur Jónsson (1780–1836), a rímur cycle on the subject of Vambarljóð was composed by the poet Sigmundur Helgason (1657–1723). No such text has come down to us.75 However, two rímur cycles on the subject are preserved from the eighteenth century.

The manuscript ÍB 895 8vo, written in 1792, preserves Rímur af Signýju Hringsdóttur by one Þórður Pálsson who is otherwise unknown. The text has some relationship with the L version of Vambarljóð — Alþrúður is said to be from Hungary.76 The text is also partially preserved in Lbs 2324 4to.

In 1781, the poet Helgi Bjarnason (ca. 1730–84) composed another cycle also called Rímur af Signýju Hringsdóttur. This is preserved in two manuscripts, Lbs 985 4to and JS 579 4to. Here, too, Alþrúður is said to be from Hungary.

Finally, a prose fairy-tale, Sagan af Signýju Vömb, was recorded from Guðrún Ólafsdóttir (ca. 1791–1862) in 1856.77 This version also shares some details with the L version of the poem — such as a curse turning Yrsa into a cat.

Some other Icelandic fairy-tales also feature princesses cursed by their stepmothers into the form of a stomach and in each case the curse is lifted by sleeping with a prince. One such tale is Hildur góða stjúpa og veltandi vömb which was recorded from the prolific storyteller Guðríður Eyjólfsdóttir (1811–78).78 Another is Gorvömb, which was first recorded by Þorvarður Ólafsson (1828–72)79 who did not specify an informant. Another Gorvömb tale with similar content was recorded on tape from Katrín Valdimarsdóttir (1898–1984) in December 1971 or January 1972. Katrín was unsure whether she had learned the story from Járnbrá Einarsdóttir (1871–1961) or from Hólmfríður Sigurðardóttir (1833–1913), Katrín’s grandmother.80

When Einar Ól. Sveinsson published his classification of Icelandic folk tale types he did not find a suitable pre-existing type for Vambarljóð and related tales so he added the tale type 404*. He mentions that he had himself heard the story long before from the old woman Steinunn Runólfsdóttir81 in Vestur-Skaftafellssýsla — adding yet another female storyteller known to have had the story as a part of her repertoire. Einar adds that he had forgotten most of the story but did remember the stomach saying at the wedding that she had often seen a weeping bride but never a weeping groom.82

The first recording of Vambarljóð which we can definitely establish took place in 1699–1700 and the poem then written down shows every sign of medieval origin. The story caught the attention of multiple poets and in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries there were still old ladies who could tell tales of resourceful princesses who were cursed to appear as a stomach. Anyone who wants to delve deeper into this tale has plenty of material to work with.

About this edition

The objective of this edition is to present the V, J and Þ versions of Vambarljóð faithfully and separately. In the case of the V text, the fact that we have four independent manuscripts allows us to reconstruct their lost written archetype *V with some precision. In the cases of J and Þ we are mostly dependent on single sources. I have resorted to conjectural emendation in a few places where the preserved text appears untranslatable and corrupt and a plausible restoration suggests itself. A further few conjectures for which a reasonable case could be made are suggested in the apparatus.

The text is diplomatic and follows the punctuation and capitalization of the manuscripts though I have intervened to begin each strophe with a capital letter and end it with a full stop. As it happens, the spelling of V1 is rather close to that of normalized Old Norse or modern Icelandic and the spelling in Þ is also helpful in marking vowel distinction. The spelling of J is typical for a manuscript written in the eighteenth century.

The translation aims for a relatively literal style, similar to that used in the Skaldic Poetry of the Scandinavian Middle Ages. When the different versions have identical wording I have aimed to use identical translations and when the versions have the same meaning but differ slightly in the choice or order of words I have tried to vary the translations a little as well.

Manuscripts used

V1 = NKS 1141 fol., 18th century (basis of V edition)

V2 = JS 405 4to, written in 1819

T = Thott 489 8vo, 18th century

T* = the first version of the poem in T, only three strophes

I = JS 80 8vo, ca. 1800

J = JS 406 4to, 1732–41

J* = Thott 489 8vo, single leaf at end, 1732–41

JH = Jón Helgason’s transcript of J

Þ = NKS 1894 4to, late 18th century (basis of Þ edition)

154 = AM 154 V 8vo, ca. 1700

430 = JS 430 4to, early 19th century

985 = Lbs 985 4to, mid-18th century

1894 = NKS 1894 4to, late 18th century

Manuscripts known with certainty to have existed

*V = a lost book of fornkvæði written in Vigur in 1699–1700

*Þ = pages lost from AM 154 8vo after Þ was made, ca. 1700

More hypothetical manuscripts

*L = the original manuscript of the L version

*forn syrpa = the claimed source of the L version, presumably dating to the second half of the 17th century; this, or a related manuscript, may have also served as the exemplar of *V

Figure 5: A possible stemma of the manuscripts of ‘Vambarljóð’.

176. Qvæðe / kallað / Vambar lióð (V version)

V-1 (J-1)

Sat *gullaudigur gylve að lande

sá er hǫlldar hríng kǫlluðu

konu átte hann sier kynstórrar ættar

kappsamr konungr kiærn að flestu.

A leader, wealthy in gold, held the land, the one whom men called Hringr. He had a wife of a noble family — that vigorous king, wise in most things.

Title: 176 Vambarliód, V2 1.1 gullaudigur: so V2, gullaudugur TI, gullauðgr V1 1.7 konungr: kongur V2, gramr I

V-2 (J-3)

Ól sier dǫglingr dóttr eina

þá er Signýiu *seggir nefna

hafðe hvors slags hannyrð numið

v́ng auðarlín átta vetra.

The monarch had one daughter, whom men call Signý. She had learned every sort of needlework — that young Lín of wealth [woman] — by the age of eight.

2.4 seggir: so V2TI, segir V1 2.6 hannyrð: handyrd V2

V-3 (J-2)

Svo var ágætleg æfin hióna

að hvort þeirra ǫðru heiðrs leitaðe

enn er kongs konu kvǫldu verkir

hýr varð hlaðzsól að hyliast molldu.

The life of the married couple was so excellent that each of them sought honour for the other. But after the king’s wife was tormented by pain the gentle headband-sun [woman] needed to be covered with earth.

V-4 (J-*5)

Geck á háfan haug alþrúðar

morgin serhvorn mætr landreke

enn fyrir hilmi á margan veg

tignarmenn hans telia fóru.

Every morning the esteemed land-ruler walked upon the high mound of Alþrúðr. But the nobles came to plead with their king in many ways.

4.5 hilmi: mildíng, Jón Sigurðsson’s conjecture

V-5

Fagrvaxin geck við fǫðr að mæla

og vm háls grami *hendur lagðe

skunda til skemmu skatna drottinn

mier er tíðt við þig tafl að efla.

The shapely one went to speak with her father and she laid her hands around the neck of the king: ‘Hurry to the bower, lord of men! I would like to play tafl with you.’

5.4 hendur: so V2TI, hǫndur V1 5.8 tafl: chess or another board game

V-6 (Þ-1)

Hǫrva heim aftr *hilmers dótter

og haf þú þǫck fyrir þína gaungu

mey veit eg ongva ne manns konu

er *bỏls stǫfum *bregdi mínvm

‘Go back home, princess, and thank you for your visit. I know no maiden nor man’s wife who might alter my baleful staves.’

6.2 hilmers: so V2T, hilmer I, hilmis V1 6.4 bỏls: so V2, bóls V1, bøl TI 6.8 bregdi: so V2TI, bregða V1

V-7

Hier sit eg hiá þier og siá þyckiunst

að muner siklingr fyrir svikum verða

giǫrir þú bǫl mikið barni þínu

*þó má skiǫlldungr ei við skǫpum vinna.

‘I sit here by you and I seem to see that you, lord, will be afflicted by deceit. You will do much evil to your child but the ruler cannot contend against fate.’

7.7 þó: so V2TI, þá V1

V-8

Geck v́ng meyia aftr til skemmu

var *ei lofðungs mær lett vm dryckiu

þó hún salkonur sumar gledde

með gulle rauðu og gersemum.

The young maiden walked back to the bower. The princess did not find it easy to partake in drinking though she gladdened some of her hall women with red gold and treasures.

8.3 ei: so V2TI, eigi V1

V-9 (Þ-2)

Kom þar að haugie kona gangande

þegar *hilmers mær hvarf í skemmu

kvadde hún ǫðling með orðum blíðum

sit þú hilmir heill með huga glǫðum.

A woman came walking to the mound when the princess returned to the bower. She greeted the king with sweet words: ‘Sit in good health, lord, with a happy mind.’

9.3 hilmers: so V2TI, hilmis V1 9.8 með: i V2

V-10

Leyfðr konungr leit ecki við

þó sá hann lióma á loft bera

seg þú en þýða þitt nafn grame

má eg *ei við þig mæla fleira.

The praised king did not turn his head yet he saw a beam of light in the sky: ‘Tell, kind one, your name to the king. I can speak no more to you.’

10.7 ei: so V2TI, eigi V1

V-11 (J-*3)

Ýrsa eg heite og er jǫfurs dótter

hef eg margt numið er menn *ei vita

spurt hef eg alllítt hylmir heilan

og mun eg brádt á því bætur vinna.

‘My name is Yrsa and I am a ruler’s daughter. I have learned many things that people do not know. I have heard that the king is not well at all and I will soon remedy that.’

11.1 Ýrsa: Irsa V2T (here and elsewhere) 11.4 ei: so V2I, eigi V1 11.7 mun: mon V2 11.7 brádt á: brádla V2

V-12 (J-*8)

Far heim til hallar hellst miǫg er framorðið

þar muntu góða gisting fánga

það er flagða háttr að fara miǫg síð

nú tel eg sólu setta vandlega.

‘Go home to the hall, it is getting very late. You will get good lodging there. It is the way of troll-women to go about very late. Now I reckon the sun has set completely.’

V-13 (J-*6, Þ-3)

Hryste hún sínar handagiǫrver

að hraut víndrope á vǫr grami

fýsti nú millding meira að drecka

þá gaf hún honvm horn fullt miaðar.

She shook her gloves so that a drop of wine fell onto the king’s lip. Now the monarch desired to drink more — then she gave him a horn full of mead.

V-14 (J-*7, J-*4)

Drack af kalke kóngr víðrisinn

að til Alþrúðar eckert munde

setst niðr hiá mier og seg tíðinde

þvíað margt við þig mæla eg villde.

The renowned king drank from the goblet so that he did not remember Alþrúðr at all. ‘Sit down by me and tell me news for I would like to say many things to you.’

14.2 víðrisinn: hapax legomenon, probably a corruption of ‘vígrisinn’, cpr. gramr vígrisinn in Grípisspá

V-15

*Ei vil eg sikling sitia í hiá þier

skal eg til hallar heim fyrir aftan

þá tók hilmer í hǫnd vífi

og til borgar heim brátt skunduðu.

‘I do not want to sit with you, lord. I must go home to the hall before evening.’ Then the prince took the hand of the woman and they hurried to the castle.

15.1 Ei: so V2T, Eigi V1 15.1–2 Ei vil ec hiá þer Sikling sitia V2, Sist vil eg hiá þier sitia konungur I

V-16

Gack í ǫndvegi æðra að sitia

eig svo við mig át og dryckiu

ǫngvum skal það ýta hlýðast

*af hǫfðe þer hár að blása.

‘Come sit in the nobler high-seat and have food and drink with me. No-one will be suffered to blow a hair off your head.’

16.6 hlýðast: hlida TI 16.7 af: I, á V1V2T; the phrase blása hár af hǫfði occurs in multiple Old Norse prose texts and always with the preposition af, while á appears meaningless

V-17

Allz ǫngvum var hún Ýrsa í þocka

þó kvaðst ræsir einn ráða vilia

lǫgðust síðan í sæng eina

óbrúðarleg mey og jǫfr siálfr.

Yrsa was to no-one’s taste, yet the king said that he alone would decide. Then that unbridely maiden and the ruler himself lay down into one bed.

V-18 (J-*2, Þ-5)

Frá eg hún Signý með salkonum

veðrblíðan dag geck epli að velia

og er hún var v́ti ein á skógie

þá kom hún Ýrsa þar að gangande.

I heard that Signý went one fine day with her hall women to pick apples. And as she was alone out in the woods then Yrsa came walking.

18.3 geck: om. V2

V-19 (J-4, Þ-6)

Ángr er mier að því meira enn mikið

að þú fegre ert flióðe hveriu

víf skalltu hafa vambar líki

og úr kvǫl þeirre komast alldregi.

‘It bothers me more than much that you are fairer than every girl. Woman, you shall have the shape of a stomach and never escape that misery.’

V-20 (J-5, Þ-7)

Vlfar þig skulu og ǫll skógar dýr

kallt griót og steinar kvika slíta

vtan leggir mier líkn nockra með

vm dapurlega æfe mína.

‘Wolves and all forest beasts, the cold rocks and the stones shall shred you alive unless you also grant me some mercy for my sad life.’

V-21 (J-7, Þ-8)

Það skal til líknar língrundin þier

ef að þig konungsson kaupir mundi

og villde til blíðrar brúðkaup giǫra

enn ætla þig þó óvætte vera.

‘It will be a mercy for you, linen-ground [woman], if a king’s son buys you with a bride price and wants to wed the sweet one and yet thinks you a monster.

21.4 kaupir: kaupa V2 (and J)

V-22 (Þ-9)

Ef svo ólíklega verða mætte

skal bráðr bane bíta Ýrsu

enn Hríngi *kongi harminum brugðið

að honvm verðe *ei neitt að ángre.

In that unlikely case, sudden death shall befall Yrsa and king Hringr be released from sorrow so that nothing will grieve him.’

22.2 orðit gæti, Jón Sigurðsson’s conjecture 22.5 kongi so V2TI, konungi V1 22.7 ei: so V2TI, eigi V1

V-23 (Þ-10, J-*9)

Vallt síðarla vǫmb til heiðar

enn Ýrsa geck heim að hǫllu

sagðe hún hilmi hvarf Signyiar

enn hann kvaðst í því allz enkis sakna.

The stomach rolled late to the heath and Yrsa walked home to the hall. She told the king that Signý had disappeared but he said that was no loss to him.

V-24

Kom þar af mǫrku mær aðrennande

sem liúfr konungr lǫndum stýrðe

ýtum þótte hann Ásmundr vera

í fornum sið frægr snemmindis.

The maiden came sliding from the wilderness into lands ruled by a beloved king. Ásmundr was considered famous at a young age during the days of the old religion.

V-25

Móðr átte hann sier með landreka

sú var veigaþǫll vitr og hyggin

hún stýrðe lǫndum og lýði víða

þegar lofðúngar í leiðangri vóru.

The land-ruler had a mother. That fir-tree of beverages [woman] was wise and intelligent. She ruled widely over the lands and the people if the princes were on an expedition.

V-26 (Þ-11)

Karl hefr búið nærre *kongs velldi

sá er auðæfi átte lítil

hann var genginn vm grænar follder

geitur heim reka og gamlar kýr.

A man who had little wealth lived near the king’s estate. He had walked over green ground to drive home goats and old cows.

26.2 kongs: so V2TI, konungs V1

V-27 (J-8, Þ-12)

Vǫmb sá hann liggia vndir viðar runni

sem úr nýdrepnu nauti være

studde að framan fæti sínvm

þá reð mær við hann margt að ræða.

He saw a stomach lying under a shrub in the woods — as if from a freshly killed bull. He touched it in the front with his foot. Then the maiden came to speak many things to him.

V-28 (J-9, Þ-13)

Hlíf mier hýr faðer og hygg að eg mune

minne móður miǫg þǫrf vera

eg kann að birla og búa að gulle

enn ómagie ecki þickiunst.

‘Spare me, kind father! And consider that I will be very useful to my mother. I can fill cups and decorate with gold. I am no freeloader.

V-29

Haf þig heim aptr heilla góðe

enn eg mun geyma geita þinna

eg skal hvorn dag hiarðar gæta

enn þið sæl megið sitia heima.

Go back home, dearest, and I will keep your goats. I will watch over the herd every day while you two sit happily at home.’

29.3 mun: mon V2

V-30 (Þ-14)

Karl skundaðe til húss þaðan

fann nú kerlingu káta sína

sagði hann henne slíkt er hann visse

enn hún kvað ser *ei vndralaust vera.

The man hurried to the house from there and found his cheerful old lady. He told her what he knew and she said that this seemed wondrous.

30.7 ei: so V2TI, eigi V1

V-31 (J-10)

Mær rak jafnan hiǫrð kerlingar

það er ólogieð í akur konungs

beitte hún þar henne hvorn dag *at ǫðrum

og giǫrðe fylki fiártión mikið.

The maiden constantly drove the old lady’s herd — this is no lie — to the king’s field. She had it graze there one day after another and did costly damage to the ruler.

31.6 at: so V2TI, af V1

V-32 (J-13)

Heim kom að hausti horskr stillir

með allmyklu ýta mengi

heitt var munngát á móti gram

enn ǫlkonur ǫðling fǫgnuðu.

In the fall the wise king came home with a great host of men. Beer was prepared for the monarch and the ale-women celebrated the prince.

V-33 (J-13)

Frettu að frægan hvorsu farið hefði

enn lofdúngr let vel yfir

spurðe á móte margs fróðlega

eða er hier nockuð nýtt í frettum.

The famous one was asked about his journey and the prince declared it successful. He asked intelligently in return: ‘Or is there anything new to report here?’

33.3 lofdúngur: so V2T, lofdángr V1

V-34 (J-15, Þ-18)

Illt er vndrum eptir að fretta

og þó er enn verra að vita af sínum

beitt hefr alla akra þína

mær kerlingar og er slíkt mein mikið.

‘It is bad to enquire about wonders and yet it is worse still to know them from sight. An old lady’s maiden has been grazing all your fields and causes much harm.’

V-35 (J-16)

Menn þickist þier mikilla burða

og oflátar ongvum minne

enn hafið þó ecki ellt úr garðe

kerlingar jóð og keyrt med hǫggum.

‘You consider yourselves able men and you are second to none in showing off. Yet you have not chased an old lady’s child from the estate and driven her away with blows.’

V-36 (J-17)

Reiðr geck þaðan recka drottinn

og bað þá alla eftir að sitia

vallt að honvm vǫmb óþvegin

vertu hilmir heill með huga glǫðum.

Angry did the lord of men walk from there and he asked all of them to remain behind. The unwashed stomach rolled up to him: ‘Be well, lord, with a happy mind.’

36.8 glǫðum: gódum V2

V-37 (J-18, J-26, Þ-21)

Hvor leyfði þer *liótvaxinn mær

að beita alla akra mína

far heðan aftr heillinn góðe

eg mun í kvǫlld heim helldr síð koma.

‘Who allowed you, ugly-shaped maiden, to graze all my fields?’ — ‘Go back from here, dearest, I will come home rather late tonight.’

37.2 liótvaxinn: so V2TI, líttvaxin V1 37.6 góðe: the masculine form of the adjective indicates that the king is addressed

V-38 (J-19)

Þá reð að reiðast recka drottinn

og laust hana hende sinne

mátte *ei leysa lófa frá kvistum

svo var buðlúngr við brǫgð kominn.

Then the lord of men became angry and struck her with his hand. He could not release his palm from the branches. Thus the prince was tricked.

38.5 ei: so V2TI, eigi V1

V-39 (J-20, Þ-20)

Vallt óþvegin vǫmb til nauta

þar varð ǫðlingr eptir að darka

seig þú sámlituð siklingi það

hvað eg skal til vinna að við skilium.

The unwashed stomach rolled to the bulls and the king had to trudge behind. ‘Tell the prince, dark one, what I should do to separate us.’

V-40 (J-21, Þ-19)

Hier skalltu alla æfe þína

buðlúng við mig bundin vera

engi maðr skal að því giǫra

fyrr enn við afgǫmul ǫndumst bæðe.

‘You will be bound to me all your life, lord, and no-one can do anything about it until the both of us die in ripe old age —

V-41 (J-22)

Vtan þú biðier mín bauga deilir

og eftir mier egir að ganga

svo skalltu brúðkaup búa vandlega

sem þú *kóngsdóttur kaupa munder.

— unless you propose to me, divider of rings [man], and seek me. You shall prepare the wedding as carefully as if you were marrying a princess.’

41.7 kóngsdóttur V2T, kongs dótter I, konungsdótter V1

V-42

Gramr kvað ecki úr góðu að ráða

þó kaus vísir vomb að eiga

hellt heim þaðan horskr stillir

var *ei lofdungi lett vm dryckiu.

The prince said that there was no good choice and yet the ruler decided to marry the stomach. The wise king went home from there. The monarch did not find it easy to take part in drinking.

42.7 ei: so V2TI, eigi V1

V-43

Að spurðe en hvíta *hilmers móðer

hvað til ógleði jǫfri være

hann í hlióðe henne sagðe

gef mier íborið eitur að drecka.

The white mother of the king asked what was giving the prince displeasure. He told her quietly: ‘Bring me blended poison to drink.’

43.2 hilmers V2T, hilmer I, hylmis V1 43.6 sagðe: allt sagdi V2

V-44 (J-23)

Hvað er svo ólíklegt orðið vm *hilmer

að þú villt fylkir fiǫrvi týna

siá munu reckar ráð betra til

enn þennan kost þigg eg eigi.

‘What unlikely thing has happened to the king that you, lord, want to lose your life? Some better counsel will be found. I will not accept this option.’

44.2 hilmer: so V2, hilme T, þig V1 44.4 fiǫrvi: fiỏri V2I

V-45

Illt er vndrum eptir að fretta

þó er enn verra vita *á sýnum

ef eg skal eiga ýr við grímu

þau hafa fádæmin flestu vm ollað.

‘It is bad to enquire about wonders, yet it is worse still to know them from sight. If I shall have ýr við grímu it is mostly caused by abnormal events.’

45.4 á so V2TI, að V1 45.6 ýr: the word is underlined in V1 but probably not by the original scribe, yr V2TI 45.6 ýr við grímu: obscure, see commentary on textual difficulties

V-46 (J-27, Þ-22)

Velltist vm vrðer vǫmb óþvegin

og fyrir hasæte hylmirs sínvm

ser hún hvar húkir *heria stiller

mátte hún *ei allra orðanna bindast.

The unwashed stomach rolled over rocky land and by the throne of her king she sees where the lord of armies is cowering. She could not refrain from speaking.

46.6 heria: so T, hermanna I, herians V1V2, Herjann is a common poetic synonym for Óðinn but it gives no sense here; the form in T is almost certainly an emendation, but it is a sensible one, cpr. herja stilli in Guðrúnarkviða III 46.7 ei: so V2TI, eigi V1

V-47 (J-28, Þ-23)

Margar hef eg vitað meyiarnar daprar

þegar flióðin voru fǫstnuð manni

hitt vissa eg *aldrei á æfe minne

að brúðguminn byggist við gráta.

‘I have known many maidens to be sad when the girls were engaged to a man. But never in my life have I known the groom about to cry.

47.5 aldrei: so V2T, alldri V1I

V-48

Hier máttu bragning siá brúðe þína